- Home

- Fariba Nawa

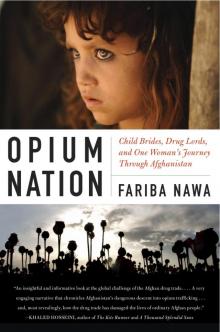

Opium Nation

Opium Nation Read online

OPIUM

NATION

Child Brides, Drug Lords, and

One Woman’s Journey Through

Afghanistan

FARIBA NAWA

Dedication

To my parents, Sayed Begum and Fazul Haq, who introduced me to the Afghanistan of the past, and to my daughter, Bonoo Zahra, who I hope will become a positive force in the country’s future

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One - Home After Eighteen Years

Chapter Two - Four Decades of Unrest

Chapter Three - A Struggle for Coherency

Chapter Four - My Father’s Voyage

Chapter Five - Meeting Darya

Chapter Six - A Smuggling Tradition

Chapter Seven - The Opium Bride

Chapter Eight - Traveling on the Border of Death

Chapter Nine - Where the Poppies Bloom

Chapter Ten - The Smiles of Badakhshan

Chapter Eleven - My Mother’s Kabul

Chapter Twelve - Women on Both Sides of the Law

Chapter Thirteen - Adventures in Karte Parwan

Chapter Fourteen - Raids in Takhar

Chapter Fifteen - Uprisings Against Warlords

Chapter Sixteen - The Good Agents

Chapter Seventeen - In Search of Darya

Chapter Eighteen - Through the Mesh

Chapter Nineteen - Letting Go

Epilogue - 2010

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

Photo Section

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

In the summer of 2003, I met a girl in an Afghan town straddling the desert who would become an obsession for me. I knew her for only a few weeks, but those few weeks shaped the next four years of my life in Afghanistan. What I remember most about her is her scared look, a gaze that deepened her otherwise blank green eyes. She was the daughter of a narcotics dealer who had sold her into marriage to a drug lord to settle his opium debt. Her husband was thirty-four years her senior, and even her threats to burn herself to death did not change her fate. A year after I met her, she was forced to go to a southern province as the wife of this man, a man who did not speak her language and who had another wife and eight children.

I met Darya on a quest to write a magazine story about the impact of the Afghan drug trade on women. Ghoryan, the Afghan district where she used to live, is two hours from the Iranian border, and the people there make their living on opium transport. In this vast district I met many men and women who were either victims or perpetrators in the worldwide multibillion-dollar drug trade, but none of them stayed in my heart as much as Darya. She had become a child bride and a servant, a casualty of the drug trade—an opium bride. Darya is a link in a long chain that begins on Afghanistan’s farms and ends on the streets of London and Los Angeles. In order to understand what happened to her, I had to understand the drug trade. I chased clues from province to province to find out who was behind the business; who its victims were; how it was impacting Afghans; and what the world, and the Afghan government, were doing to stop it.

In 2000, I made my first trip back to Afghanistan in eighteen years, during Taliban rule, to search for something I had lost—a sense of coherence, a feeling of rootedness in a place and a people, and a sense of belonging. I had many unsettled emotions toward my homeland, which I had had to flee at the impressionable age of nine. The strongest feelings were aching nostalgia and lingering survivor’s guilt, which my parents and siblings did not share. I was the youngest, with the fewest memories of the war-torn land, but I longed for it the most. All that my adopted home, the United States, offered me could not make up for the loss I felt in leaving Afghanistan.

In the process of finding ways to deal with my demons, I wanted to tell the world that the Afghan drug trade provided funding for terrorists and for the Taliban, who were killing Americans and strengthening corrupt Afghan government officials whom the United States supported. A former chief of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration called the Afghan opium trade “a huge challenge” in the world. Americans and the British are directly harmed by it. Afghan heroin is a favorite among addicts because it’s a potent form of heroin, and increasingly available.

I spent 2000 through 2007 shuttling back and forth between Afghanistan and the United States, with detours to Iran and Pakistan. The majority of my time was spent traveling through Afghanistan. During that time, I witnessed the country’s shift from a religious autocracy to a fragmented democracy and, finally, to a land at full-scale war. The result of that war has been dependence on an illicit narcotics trade, without which the Afghanistan economy would collapse. For the opium trade is the underground Afghan economy, an all-encompassing market that directly affects the daily lives of Afghans in a way that nothing else does.

Ghoryan district, Darya’s childhood home, is full of individuals and families with stories few have heard. The Afghan women who live there are not the weak, voiceless victims they are so often made out to be in the Western media. Since they see themselves as part of their family units, Afghan women rarely demand individual rights, as women, something uncommon in the West. During my time in Ghoryan, these women, including Darya, showed me just how powerful they were, and how capable of overcoming their problems.

The effect of the opium trade in Ghoryan is very real. Yet Ghoryan is not the only place where the drug trade resides. In some places, the trade is destroying lives; in others, saving them. During my time in Afghanistan, I was drawn to cities and villages where some chose this illegal business while local warlords force others to dive into it. Opium is everywhere—in the addict beggars on the streets, in the poppies planted in home gardens, in the opium widows hidden from drug lords in neighbors’ homes, in the hushed conversations of drug dealers in shops, in the unmarked graves in cemeteries, and in the drug lords’ garish opium mansions looming above brick shacks and mounds of dust. The dust is a reminder of the destroyed land that opium money seems unable to transform into cement, asphalt, or water.

In this book, I’ve changed many of the names to protect the people I write about. In Afghanistan, revealing identities does not just invade privacy but also endangers lives. I also try not to focus on the ethnic rivalries in Afghanistan that have, to my mind, been overemphasized and overanalyzed in the West, though it is impossible to ignore them. After September 11, 2001, many Americans were anxious to know whether I was Pashtun, Tajik, or another minority group. I’d stare at them confused and say simply that I was from Herat.

The years I spent working in Afghanistan were the most dangerous and exciting of my life thus far. The action-packed sequence of events I experienced there tested my will to live and set me on a journey to see if the passion I held for my birthplace and its people was rooted in the present or lost in the past.

Chapter One

Home After Eighteen Years

Flies buzz and circle my face. I swat them away as I slowly look up to see a dozen men watching me outside the visa building. I’m standing in line at the Iranian border, waiting to cross into my home country, Afghanistan. Men stare at my face and hands. My hair and the rest of my body are covered in a head scarf, slacks, and a long coat, in observance of Iran’s dress requirements for women.

I keep my eyes to the ground to avoid the ogling. An Iranian border agent calls out my name. My hands tremble as I give him my Afghan passport—perhaps the least useful travel document in the world. I’ve hidden my American passport in my bra; Iran restricts visas for American citizens, and the Taliban are wary

of Afghan women returning from the United States.

“Where are you coming from?” the agent asks with a serious face.

“Pakistan.”

“What are you doing there?”

“I work for a charity organization.” I actually work for a Pakistani think tank as an English editor, and I’m a freelancer writing articles about Afghan refugees in Pakistan for American media outlets. I don’t share these details with the Iranian border agent, though; they would only raise more questions and delay my journey.

“What were you doing in Iran?”

“Visiting my relatives.”

He eyes me suspiciously and flips through the pages of my passport. Then he stamps the exit visa with “Tybad,” the Iranian border city, and motions me to leave.

It is late morning and a cool fall breeze hits my face. My hands stop shaking but become clammy, my stomach churns with nausea, my head spins. In just a few hours I will be in Herat, my childhood home, for the first time in eighteen years. The anticipation feels a bit like the moment before I delivered my daughter: painful, frightening, yet exhilarating.

I am accompanied by Mobin. The Taliban require that women travel with a male relative, a mahram, but I didn’t have a male relative willing to lead me to war-battered Afghanistan. In Iran, I stayed with Kamran, whose family were our neighbors in Herat. He is the son of Mr. Jawan, a retired opium smuggler, and a close friend of our family. He asked his friend Mobin to act as my mahram. Mobin, a merchant based in Herat, met me at Kamran’s home in Torbat-e-Jam, Iran. He is shy and taciturn; he shows his expressions by raising or lowering his deeply arched dark eyebrows. Mobin imports buttons and lace from Iran to sell in Afghanistan, earning about $3,000 a year. He sees his wife and eighteen-month-old son in Herat one week out of every month. Shrewd and experienced on the road, he promised Kamran he would safely guide me from Iran to Afghanistan and finally back to Pakistan.

Mobin and I walk a few yards from the Iranian side of the border and onto Afghan soil, in the town of Islam Qala. We rent a taxi with two other women; Mobin is acting as their mahram as well. Each woman is dressed in a black chador, a one-piece fabric covering the whole body. The women whisper to each other and wrap one end of their chadors over their mouths. The Taliban have banned music everywhere in the country, but our driver, a tall, unassuming man, slips in a cassette of Farhad Darya, the most renowned Afghan pop singer, and turns up the volume as we head for Herat. He risks the destruction of his tapes and a beating if the Taliban catch him. (The Taliban usually rip out the ribbons from seized video- and audiocassettes and display them in town centers as a lesson to others.) But our driver is among many Afghans who take this risk.

The taxi rolls up and down over sand dunes, lolling me back to the past. The desert we are crossing was the front line in the war when I was a child. I was nine years old the last time I crossed the path of the ancient Silk Road, when my family fled Afghanistan in 1982, during the Soviet invasion. For six hours my parents and older sister walked while I rode on the donkey carrying our belongings until we safely reached Iran, and then Pakistan. We eventually sought asylum in the United States, where I grew up in California. I haven’t stopped dreaming of returning to Afghanistan since I left. I cling to my memories of the nine years I spent there, a mixture of blissful childhood innocence ruptured by the bloodshed of war.

A bump in the road jolts me out of my reminiscences. I take out my journal and write under my black coat. The others in the car see the journal.

“How can you write on such a rough ride?” Mobin asks.

“My handwriting will be bad, but I’ll be able to read it,” I answer.

I scribble as the car jumps, rolling over a big rock. Where are we? Was it here that I cried for water for two hours under the scorching sun? Water had finally arrived, in a plastic oil container from a salty desert well. I drank and gagged, I remember, spitting the water on the donkey I was riding.

I put the journal away and look out the taxi’s dust-covered window. My view is an endless desert dotted with boulders and thorns. The taxi’s tires kick up more dust, and a rain of sand blocks the view for a moment.

Every time a man appears, either walking or in a car in the distance, the other women and I shield our faces with the edge of our head scarves.

“Don’t worry. The Taliban are scared of women,” Mobin says. “They usually stop cars with only men. The ones with women, they just turn their heads.” He’s not kidding. Many of the Taliban were orphans who grew up in Pakistani refugee camps, attending religious schools. Some have had little or no contact with women.

I close my eyes and listen to the voice of Farhad Darya.

In this state of exile

My beloved is not close to me

I’ve lost my homeland

I’ve lost my wit

O dear God

The singer laments his distance from Afghanistan; he recorded this song in Virginia. Darya is loved for his original lyrics, which invoke the nostalgia and painful experience of exile. His songs are steeped in loss, longing, and the warmth the homeland gave him. His music speaks to those inside the country as well as to the Afghan diaspora. I usually become melancholy when I listen to his music, but this time I smile. I’m no longer in exile.

I think I’m getting closer to home.

The war was in its fourth year, and my mother, Sayed Begum; my father, Fazul Haq; and my sister, Faiza, lived in our paternal family property in downtown Herat. My brother, Hadi, had already fled the country. Our home consisted of two rooms and was one of three houses built on two acres of land. The land, once emerald with gardens of herbs and vegetables, was now dry, with only a few surviving pomegranate trees and a blackberry tree. The war, the shortage of water, and the absence of a caretaker—our caretaker, Rasool, died before the war—had led to the land’s neglect. We shared the property with my father’s youngest brother, a dozen of his in-laws, my paternal grandfather, Baba Monshi, and his wife, Bibi Assia.

Baba Monshi’s name was Abdul Karim Ahrary. A renowned essayist and intellectual, he was an adviser on the drafting of Afghanistan’s constitution in 1964 and pioneered the women’s movement in Herat city in the 1960s. He established Donish (Knowledge) Publishers and was the editor of Herat’s official newspaper, Islamic Unison. His protégé was his niece, my aunt Roufa Ahrary, who started Mehri, the first women’s magazine in Herat. Our home was a meeting point for secular intellectuals to debate politics, play chess, and drink tea. Baba Monshi’s opinions were ahead of their time. He believed that women should have the right to an education and he wrote against the injustices of British imperialism and the inequalities in the Afghan government. The government first jailed him in the early twentieth century, then exiled him from Herat to Kabul. His influence had spread in Herat, which made the Afghan monarchy nervous.

By the time I was born, Baba Moshi had lost his once-vibrant capabilities for intellectual thought. When my blood grandmother Bibi Sarah died in 1967, my grandfather married Bibi Assia, who became my step-grandmother. She was a plump and petite woman, and hugging her was like wrapping my arms around a soft pillow. She dedicated her time to caring for my ailing grandfather. In his later years, Baba Monshi spent most of his hours roaming around the property, feeding his gray-and-black cat, Gorba, and giving bread to the ants in the yard. Near the end, he didn’t recognize most of his family, except for his wife, whom he sought out only when he was hungry. Bibi Assia’s biggest gripe was that Baba Monshi would not eat the meat on his plate; instead he fed it to Gorba.

Two miles from our property on Behzad Road was my maternal grandfather’s three-and-a-half-acre orchard home near Herat Stadium, on tree-lined Telecom Road. My mother would take me to Haji Baba’s house every weekend and on holidays. We would stay for several nights at a time. I recall the cheerfulness of my childhood in this home. I’d climb trees, pick fruit, and play with my dozen maternal cousins. The orchard was replete with mulberry, cherry, pomegranate, walnut, apple, peach, and orange tre

es, as well as grapevines. My grandparents also had a small barn in the back of the land, with a few cows. A narrow creek cut through the trees, and their eight-room redbrick house sat in the center of the land. The rooms were full of people. Haji Baba’s real name was Sayed Akbar Hossaini and he was a financial adviser for the government who traveled to other districts and provinces for work. He also wrote essays, which one of my maternal uncles, Dr. Said Maroof Ramia, compiled into a book, published in Germany in 2006, titled The Authorities of Herat. Haji Baba did not get to spend much time with his family, but Bibi Gul, my maternal step-grandmother, was hardly alone with ten children—my aunts and uncles—and a dozen grandchildren. Fewer bombs dropped near Haji Baba’s property than ours, because it was secure with the presence of the nearby police station and several government offices. The orchard there was my sanctuary.

Outside the gated properties was a lively city with horse wagons, public buses, shoppers, and a five-thousand-year history shared by the city where we lived. The city was surrounded by four-meter-high walls that hid the houses, most constructed from adobe or concrete. Five gates served as entrances and exits for the city. Herat’s older homes, including the remains of the Jewish neighborhood, were two-story structures decorated with intricate tilework and carvings, and were designed with square courtyards and fountains. Among the houses and shops were numerous architectural wonders that made the city an outdoor museum of Afghanistan, including a centuries-old fort, spectacular minarets, shrines, and mosques.

Opium Nation

Opium Nation