- Home

- Fariba Nawa

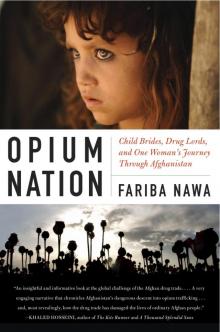

Opium Nation Page 18

Opium Nation Read online

Page 18

My mother’s barometer for people’s status has often been appearance, which is common among Afghans of all generations. Snazzy Western clothes, such as miniskirts and flared jeans, as opposed to traditional dress, were an indication of the freedoms men and women had before the mujahideen takeover in 1992.

She exits the airport terminal elegantly and smiles when she sees me. She holds out her arms, and I throw myself into them. Her eyes are tearful. I hand her a tissue. She pays the porter carrying her bags ten dollars, three times more than he usually receives. The driver who’s brought me to the airport to meet her loads my mother’s suitcases into the van and we head to the Karte Parwan house I share with a British man and American woman. I’ve taken a job working as an international consultant for an Afghan news agency called Pajhwok; my roommates also work for the agency. Our task is to provide on-the-job training to local journalists in the basics of reporting and writing a story. I moved to Kabul two months before my mother’s visit, to join the thousands of repatriating exiles from Western countries aiding in the reconstruction of Afghanistan. I am no longer a visitor or a guest in my homeland. But I’m delighted that my mother is my guest for a few nights.

We haven’t seen each other for three months and I miss her warmth and her cooking. She has come to Kabul en route to Herat to see her relatives. Unlike my father, whose relatives fled, my mother still has many cousins and uncles living in Herat. My father did not want to return again after his 2002 trip.

“You look happy,” my mother says.

“I am,” I agree, holding her hand. “I like living in Kabul. It’s more liberal than Herat.” We’re sitting in the back of the car taking in the city.

“Am I really in Kabul?” my mother asks. “It’s so crowded, so many cars, so much smog. Are these big posters for the elections?”

“People are very excited about the first presidential elections. Twenty-three candidates are running, even a woman,” I tell her.

“God punish the Soviets for coming here and ruining our lives. I hope whoever gets elected can do something for this city.”

My mother has arrived in Kabul at the height of hope in post-Taliban Afghanistan. The Bush administration has declared the war in Afghanistan a success and American resources and military power are being sent to volatile Iraq. The country is relatively peaceful, aside from small skirmishes among the Taliban and coalition troops. The biggest problem is the former mujahideen, who, with American support, are enjoying a comeback. Many of them have returned to extortion, drug dealing, and kidnapping. They kidnap foreign aid workers and Afghans who work for foreign organizations, demanding ransoms. Several of the cabinet members are mujahids, and many of the presidential candidates made a name for themselves fighting the Soviets. Reconstruction is in full gear—bulldozers, freshly poured cement, and construction workers fill the capital’s streets—creating deafening but welcome noise. The Kabul-to-Kandahar highway was rapidly built to demonstrate nation building just in time for this year’s Afghan and U.S. presidential elections. The corruption in the government, the burgeoning opium trade, and a potential Taliban comeback are topics few Afghans want to focus on. The general attitude is that things are going to be better than they have been since 1978. The uplifting mood does not infect my mother; she has yet to accept postwar Kabul. Everywhere we go she tells me how it was in the 1960s and ’70s, the golden era of peace.

“Women who wore burqas were known to be pickpockets in Kabul then,” she says as we stroll uphill on a Kabul street. “One of them stole four thousand rupia [forty dollars] from my purse in a shop when I went to visit at that time. I wore a burqa in Herat, but in Kabul, I could show my face and be fashionable. But most important, it was safe. We could go anywhere and stay out late and walk alone in the streets, take the bus. I never felt in danger.”

Her heels fall in the cracks of the road as we walk to the nearby shops one afternoon. “Wee Khoda [Oh God], you can’t even walk in this town anymore without being injured,” she complains, holding the tail of her head scarf over her mouth to block the pollution.

I’m as annoyed as I was with my father’s criticism. I saw Kabul during the reign of the Taliban, in 2000, and the city was like a graveyard. People did not speak out of fear, there was no construction being done, and the only women I saw on the streets were beggars. The Kabul I’m living in now is a city waking from the dead, on the brink of change.

“Madar, why don’t you wear more comfortable shoes.”

My father gave my mother the name Nafasgul, meaning “the breath of a flower,” as was tradition in their generation—husbands often gave their wives endearing nicknames when they first married. But my mother doesn’t like Nafasgul or her birth name, Sayed Begum. She’s a member of an Afghan elderly women’s group in Fremont, California, and the women there began calling her Saida, which in Arabic means the female descendant of the Prophet Mohammed. “I think it’s my right to change my name if I don’t like it,” she tells me. “Saida is much more meaningful than my other names.” Perhaps she’s right. After all, she does come from a Said family who traces their ancestry to the Prophet Mohammed. It’s one of my mother’s only attempts at asserting her independence.

Saida has spent her seventy-three years of life being a mother and wife, with a short stint teaching elementary school. The first time she saw my father was on their wedding night, when she was fifteen; their families arranged the marriage. She is a social butterfly who hates to miss a party, and her list of telephone numbers, all of which she has etched in her memory, is longer than my list of six hundred contacts. Saida is kind to a fault, putting others before herself, even when she shops; she keeps a chest full of gifts ready to hand out to friends and family for weddings, housewarmings, and birthdays. She tailors the gifts of clothing with her Singer sewing machine. Ever since I can remember, Saida has been ill, first with an incurable stomach ulcer, then with numerous sicknesses, including a slipped disc, which occurred when she immigrated to the United States. But her ailments have not dampened her desire to connect with others and to enjoy life. No matter how sick she is, Saida will dress up and put on a light coat of lipstick and foundation. She owns a small sterling silver container filled with black kohl, sorma, and a silver stick that she dips in the container and uses to draw a narrow line of black on the bottom lid of her cocoa-colored, doelike eyes. Her expensive head scarves are her signature fashion statement, to declare her piety and modesty. I have rarely seen my mother’s hair, except the gray bangs that neatly peek out. “My head becomes cold if I take off my scarf,” she admits to my father, giving him a gleaming white smile. She even sleeps with two layers of scarves on her head.

My clumsiness and disregard for fashion stand out when I’m with my mother. “Your mother is so beautiful and elegant,” people say, politely leaving out “What happened to you?”

Life in the United States has had its perks for Saida. She receives proper health care and has learned some words of English, which allowed her to pass her citizenship test. The clean water and food soothe her excessive need for cleanliness, and she no longer has to wear a burqa, as she did in her last years in Herat. But the loss involved in leaving Afghanistan has been immeasurable. The social fabric of her life unraveled. She was no longer able to hop in a taxi and see her parents, and she could not easily communicate with her friends and neighbors. “I feel mute when I go out,” she says.

She tried to become fluent in English, taking several courses, but she was forty-seven when she arrived in the United States, and it was a daunting challenge for her to learn a second language. She has not learned how to drive either, which has left her stuck at home, waiting for calls from the various parts of the world where her brothers and sisters are scattered. By returning to Afghanistan now, can she regain what she has lost, if only for a couple of months?

In my room at the house in Karte Parwan, I lie on the queen-size bed while my mother insists on sleeping on the red toshak (mat) on the floor. The electricity is gone for

the night and the streets are silent. The only sound comes from the small radio I own. Kabul’s media is exploding with dozens of radio and television stations and newspapers with unprecedented freedom of the press. The most popular station is Arman Radio, and tonight they’re broadcasting a two-hour special dedicated to the dramatic life and mysterious death of Afghanistan’s most renowned singer, Ahmed Zahir, the artist who revolutionized Afghan pop music, fusing Western instruments with Persian poetry. Girls screamed at his concerts, and he became a pop icon. In 1979, Zahir’s friends took him for a drive toward the Salang Tunnel on his birthday, and he was shot dead. No one was convicted. Only one man, who lives in the San Francisco Bay Area now, was with him in that final minute on that day and knows the details, but he refuses to divulge any information.

Saida and I listen to the program. Zahir’s widow is begging for the man to come forward and speak. Zahir’s songs play in the background.

“Life was so different back then,” my mom reminisces. I focus on her soft voice in the dark, closing my eyes and letting her take me back to her Kabul.

“The last time your father and I lived in Kabul was in the mid 1960s. Zahir Shah was in power. Hadi was in the third grade, and Faiza was just born in Kabul. We lived in Karte Mamureen, a decent neighborhood, renting the guesthouse of a family. There was a shrine in the middle of the courtyard. We had two rooms, a kitchen, a squat bathroom, and twenty-four-hour power. We had an electric heater in the winter; it was enough to warm us. Your dad was a translator for the Russians at inhasarat [Afghanistan Bureau of State Monopolies]. The Russians were here providing aid. Back then he could speak English, Arabic, and Russian. Now he barely mumbles Farsi.

“We were there for three years. We ate meat and rice, and had every seasonal food available to us. We were comfortable and never bored. I went to see our relatives by bus or taxis, or they would pick us up in their cars. Rich folks had cars back then. The men talked politics and I remember it was often centered on Iran. Most women my age were homemakers. We wore head scarves and fairly modest clothing, but the young women wore miniskirts and had beehive hairstyles. I wore bell-bottoms and coats in the winter.

“Hadi was enrolled in Aisha Durani School and it was coed. He came home with sewing assignments. I took care of the house and the kids in Kabul. We did not have servants like we did in Herat, but I didn’t mind because we had our own place. We didn’t have to live with the extended family.

“Your father and I went to the cinema and watched Indian movies. We used to go shopping; most of the merchandise was made in the Soviet Union. There was no security issue back then. People’s biggest fear was pickpockets.

“I entered the continuing education school at the women’s center and studied up to the seventh grade. I wanted to finish high school so I could get my teaching degree and be a teacher in Kabul. But my school was transferred to Paghman; it was too far for me to travel.”

Her voice trails off as she begins to snore lightly. I turn off the radio and try to sleep, wishing I could’ve seen my mother’s Kabul.

The next morning, Saida excitedly wakes up and gets ready for another flight. She is going home to Herat, to see relatives she has longed to unite with for two decades.

After I drop my mother off at the airport, I face the Kabul that my mother has been anxious to exit.

From 2005 to 2010 the number of opium addicts in Afghanistan increased 53 percent and the number of heroin users doubled. The rise in addiction is a reflection of the drug industry’s boom. Women and children account for a quarter of the addicted. Four out of ten Afghan police recruits test positive for drugs. Some of the women addicts are farmers who plant opium; others include carpet weavers who numb the pain in their fingers by smoking opium after working inhumane hours. Children become addicted inhaling the secondhand smoke from their parents, and some parents give opium to calm their children. In some districts, especially in Badakhshan, entire families are addicted. Men who are addicted suffer from joblessness and poverty. Afghanistan traditionally had a minute number of addicts, mostly among the Turkmen ethnicity and the sick, who used the drug to dull their pain. But the neighboring countries dictate the culture of addiction—Afghan refugees who work as laborers in Iran, Pakistan, and the Central Asian states become addicted, and when they repatriate to Afghanistan, they import their addiction. The country has a growing market of opium to supply its own people. Drug pushers encourage addiction because they recruit addicts to become couriers. All the addicts normally get in return is a gram of heroin.

Nejat Center is one of forty-three addiction treatment centers for the estimated one million addicts in Afghanistan. The treatment centers have the capacity to treat ten thousand addicts at a time. Established in 2003, Nejat is one of the country’s first treatment centers. In 2010 the Interior Ministry opened a one-hundred-bed center for policemen, and many more centers are needed to treat the rising number of addicts. The increasing number of AIDS cases—confirmed at two thousand, but health experts estimate the figure to be much higher—has prompted centers such as Nejat to hand out clean hypodermic needles to intravenous drug users. The Afghan counselors and doctors at Nejat have formed a rehabilitation program for men and women, most of whom are repatriating refugees from Pakistan and Iran. They treat about twenty patients a month but have a 70 percent relapse rate. There are ten beds for the resident addicts, but much of the group’s work is outpatient. The men sit in a circle on a mat and sing, exercise, and talk about their addiction problem. When they leave, Nejat counselors, many of them volunteers, follow up with the patients after a year to monitor how they are recuperating. The center also offers them job training and loans for small businesses, which may be shining shoes or selling fruit from a cart.

Down a muddy road in Kabul, Nejat Center is located behind the gates of a large house. Inside, photos of the men the center has treated hang on a wall. One is particularly disturbing: a homeless man with worms in the back of his head. Next to it is a photograph of the same man looking healthy and cured. It’s an effective visual. Three thousand addicts are on Nejat’s waiting list.

Riaz, a smiling charmer in his twenties, is a recovering addict at Nejat Center. He says he was a construction worker in Iran and that he began smoking opium at first to fit in with the rest of the laborers.

“Opium didn’t give me enough of a high so I switched to shooting up heroin,” he says nonchalantly. He raises his sleeve to show me the track marks on his arm. “We realized that if we’re high, we can work more hours and make more money that way. But it got to the point where I spent all my money buying drugs.”

Riaz’s tale is all too common in Afghanistan.

Nejat also treats women, as the number of female addicts in the country has continued to rise. In Kabul’s old city, on the hills of Deh Afghanan, every other household, including men, women, and children, abuses opium, Nejat counselors say.

Bibigul is plopped in her usual spot near the window looking down on old Kabul, a neighborhood called Mystics and Lovers. The alleyways contain mud-brick homes built a century ago that are falling to pieces. She can see the sewage running through the open canal; its stench overpowers her nostrils. Even though it’s eighty-two degrees in the small room where she drinks green tea, she shuts the window. She alternates between the heat and the odor, depending on how long she can tolerate either of them, opening and shutting the green-paneled window.

“Why can’t you just leave it open?” her daughter-in-law Parizad asks.

“It stinks,” she shoots back.

Sarah and Farah, her two green-eyed grandchildren, chase each other around the room laughing.

“Bibi, open the window, it’s hot in here!” they both chime.

Defeated, Bibigul opens the window a crack. She has to change positions, the biggest challenge of the day for her.

“Stop being naughty and help me get up,” she affectionately shouts at the girls.

They both run to her and hand over her cane. Sarah, six years ol

d, holds her right arm, and Farah, eight years old, takes her left, and they both lift the 170-pound woman. Bibigul, who is in her fifties, pants and heaves. She takes one step forward and the other foot stays still.

“Come on, Bibi, you can do this. You’ve done this before,” Farah encourages.

The support helps Bibigul walk and breathe with less discomfort. It is her achievement for the day. She has to go to the bathroom five times a day, and each time, the walk feels like a hike through the Hindu Kush. Her knees ache, her back twinges, her legs quiver. She knows what it would take to make it less painful, but today she doesn’t have any of her pain relief.

“Last night the forty-step walk was a breeze. But last night I got to suck on that lentil-size piece of opium and feel the soothing calmness and absolute peace. I don’t have the fifty rupia [one dollar] to buy it today,” she says. “I’ll have to ask Mirza, my son, for the money. He got up at the crack of dawn to dig a grave. The family of the deceased will probably call me soon to wash the body.”

They are a team, mother and son, body washer and gravedigger. That’s how the family makes a living.

“I wonder if the family of the deceased has the money to pay my fee [four dollars]. Then I can send Hassan, the boy next door, to fetch me my medicine.” Her “medicine” is a dime-size bit of opium wrapped in a small plastic bag.

“I need my medicine,” she mumbles to me under her breath. “Can you get me some?”

I shake my head.

“Which one—the one the doctor gave you or the one Hassan brings?” Parizad asks.

“What good have the doctor’s pills done for me!” Bibigul shouts. “I need my real pain reliever. People say it’s bad for you, but nothing has ever made me feel better.”

Opium Nation

Opium Nation